|

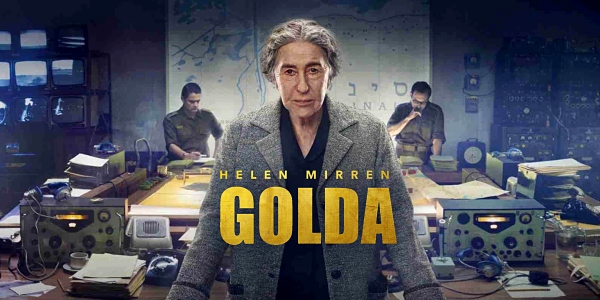

Welcome to The Helen Mirren Archives, your premiere web resource on the British actress. Best known for her performances with the Royal Shakespeare Company, "Prime

Suspect" and her Oscar-winning role in "The Queen", Helen Mirren is one of the world's most eminent actors today. This unofficial fansite provides you with all latest

news, photos and videos on her past and present projects. Enjoy your stay.

|

Celebrating

10 years

on the web

|

In Excalibur John Boorman achieves a true epic vision and grandeur, creating an alternately wild and lyrical canvas of a world way out of reach. With his co-scenarist, Rospo Pallenberg, he has gone back to the finest rendition of the King Arthur myth, Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, and drawn, with great faith, from its ingenuous powers. But since Arthur, his magic sword Excalibur, his knights and their search for the Holy Grail are the stuff of familiar legend and readily consigned by modern tastes to the functions of the action genre, Boorman {Point Blank, Deliverance) begins his epic fancifully and with an unbridled sense of fun closely resembling camp. Arthur’s conception through the alchemical intervention of the wizard Merlin (Nicol Williamson) and his taking the sword from the stone to gain kingship are scenes played for their rapturous mix of the outlandish and benignly prosaic. With the stunningly shot jousts and battles and Merlin’s sardonic mumbo jumbo, Boorman relaxes us into the narrative until we’re comfortable with its imaginative construct. And then the magic takes hold.

It’s hard to know exactly when this occurs, but before long all the great themes of the myth —loyalty, anachronism, the power of love and the utter naïveté of being human—converge like one protean, crashing chord of music. The music Boorman uses, which at first seems comically inapt and overblown — Wagner’s funeral music from Siegfried for the Excalibur theme and the sweeping love music from Tristan und Isolde for the emotionally erring Lancelot (Nicholas Clay) and Guenevere (Cherie Lunghi)—starts to make majestic sense. No other music except Wagner’s would be heroic enough to match the magnitude of the myth.

Excalibur is a miracle of pacing and seductive rhythm: we become wrapped up in the weight of human emotion through Arthur (Nigel Terry) and then watch this emotion being dwarfed by a continuing and complicated drama of forces clashing to retain what is noblest about being human. As Merlin tells Arthur, it is now “the time for men” to use their frail means to find magic and become “the stuff of future memory.” As heroic as Homer and having the wrought-iron lyricism of Wagner, the movie sends chills through you.

Excalibur gets richer as it unfolds, as though the movie rains and then pelts down pieces of gold. Alex Thomson’s lighting suggests the time and place of myth where beauty is removed to another degree, and surrounds its scenes with a sensual mist. The imagery is breathtaking: Guenevere riding on her horse through the woods near Camelot at night to her tryst with Lancelot; battle scenes glimmering with mail splashed with blood; Arthur dying after battle, as an incarnadine, embryonic sun rises behind him; Arthur’s barge, at the end, floating across still waters to the beyond.

What has threatened at the outset to be as silly as Star Wars (which purloined its basic plot elements from this myth) turns, in Boorman’s hands, into something quite stirring. After Merlin has been iced inside Time by Arthur’s revanchist half-sister Morgana (Helen Mirren) and Camelot has crumbled, the knights seek the Holy Grail to bring the country physically and spiritually back to life. When Perceval (Paul Geoffrey) brings the Grail back to the wasting Arthur, the scene that follows is worthy of any wish: Arthur and his knights setting out to do battle with Morgana’s forces while underneath flowers and growth regenerate. Movies might have been invented for such scenes.