|

Welcome to The Helen Mirren Archives, your premiere web resource on the British actress. Best known for her performances with the Royal Shakespeare Company, "Prime

Suspect" and her Oscar-winning role in "The Queen", Helen Mirren is one of the world's most eminent actors today. This unofficial fansite provides you with all latest

news, photos and videos on her past and present projects. Enjoy your stay.

|

Celebrating

10 years

on the web

|

Illicit sex and psychotic violence have become the routine ingredients of the Hollywood thriller. And when female protagonists are involved, traditionally there have been just two kinds of women: the trembling victim who is stalked into a dark dead end, and the conniving femme fatale whose wanton sexuality carries a lethal sting. But in recent years, the women-as-targets have begun to shoot back—resilient heroines ranging from Jodi Foster’s FBI agent in Silence of the Lambs (1990) to the spunky musician played by Madeleine Stowe in the current thriller Blink. At the same time, the castrating vixen has grown marginally more sympathetic. Wielding an ice pick with a self-assured sense of humor, Basic Instincts Sharon Stone was a cut above the hysterical, rabbit-boiling adulteress played by Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction. Stowe, meanwhile, seems intent on having it all. In her new thriller, China Moon, she plays a husband-killer who is both femme fatale and helpless victim.

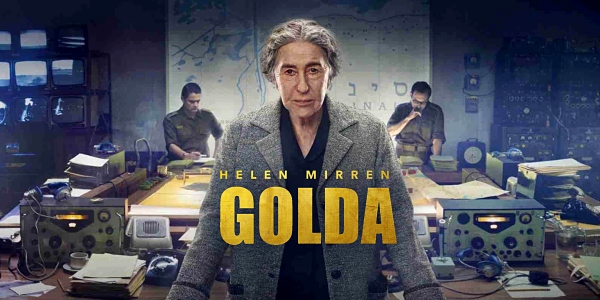

While Hollywood plays with new prototypes of women who kill, its portrayal of sex and violence remains rooted in well-worn clichés. However, three new movies by British-based directors offer less typical images of women mixed up in murder. The eyeopening documentary Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer explodes the tabloid mythology surrounding the case of a Florida prostitute who confessed to murdering seven men. In The Hawk, Helen Mirren brings grit to the role of a mentally-ill mother who suspects that her husband may be a serial killer. And in the darkly comic Romeo is Bleeding, Lena Olin does a burlesque take on the lethal woman—a sadistic gangster in a black garter belt.

The Selling of a Serial Killer is a devastating look at the circus of exploitation surrounding Aileen Wuornos, 36, who now sits on Death Row in Florida, awaiting the electric chair.

The camera follows British director Nick Broomfield’s Alice-inWonderland travels through Florida, documenting his interviews—and his deadpan negotiations with interview subjects who insist on being paid for their efforts. They include Arlene Pralle, a Christian fundamentalist who legally adopted Wuornos, and the killer’s lawyer, the utterly bizarre Steven Glazer. He claims that his client’s death is in her best interests, and Pralle concurs. “She’d be much better off in heaven,” she says. “If I had the choice, I’d go.”

Glazer becomes the film’s central figure, a personification of truth being stranger than fiction. He is a pot-smoking former musician who sells himself as Dr. Legal in TV commercials. He recommends that his client plead guilty, leaving the judge no option but to impose the death sentence. He serenades the camera with Phil Ochs songs, including a ballad about the electric chair titled Iron Lady which he has promised to sing to Wuornos before her execution. Then, quoting Woody Allen, he says his advice to his client is, “Don’t sit down.”

The movie also uncovers allegations that local police officers negotiated with the killer’s lesbian lover to sell the rights of her story to Hollywood, even before Wuornos was arrested. By the time Broomfield finally gets to interview Wuornos in prison, she seems like one of the saner characters in the movie. She is a tragic figure, the product of an abused childhood, and she claims her killings were provoked by violent customers. Whether or not she killed in self-defence, Broomfield makes it clear that she is both a

perpetrator and a victim. But his wry investigation goes beyond the issues of the case. It also serves a foreigner’s curious encounter with white-trash Florida—and a surreal excursion through the show-business novelty of American justice.

The Hawk is a taut, creepy thriller about a male serial killer on the loose in a Manchester suburb. Its fictional story has a ghoulish premise. The murderer gouges out the eyes of his victims—all of whom happen to be mothers of two children—after beating them to death with a blunt instrument. But the movie plays as a psychological drama, told through the anxious eyes of a housewife, Annie, who is brilliantly portrayed by Helen Mirren. A mother of two, Annie suspects that her husband, a travelling machine engineer

make her glamorous, give her a male ally and run her through a gauntlet of physical threats. But Annie is ordinary and alone, trapped in her own mind. Her strength is an obsessive peserverance.

Romeo is Bleeding, meanwhile, does not even go through the motions of psychological realism. It is a hard-boiled parody of film noir, featuring characters who live in that archly ironic hyper-space found only in the movies. British actor Gary Oldman (Dracula) plays Jack, a New York City cop on the take. His job is to deliver mobsters to a federal task force on organized crime. But he betrays their whereabouts to Mafia hit

named Stephen (George Costigan), is the killer. She begins to piece together clues— a missing hammer, the timing of her husband’s absences, a remark by Stephen to his brother (Owen Teale) about getting rid of a car. But Annie, who has a history of mental illness, wonders if her mind is playing tricks on her.

Produced for British television, the movie bears a striking resemblance to Prime Suspect (1992), the rivetting BBC-TV mini-series that starred Mirren as a homicide detective tracking a serial killer. The Hawk is a cruder concoction—Prime Suspect meets Diary of a Mad Housewife—and the script takes some clumsy turns. As a whodunnit, it doesn’t deliver.

But director David Hayman draws some intriguing connections between brutal horror and the needling irritations of domesticity. His camera, constantly mobile, creates nerve-wracking tension out of the most mundane situations. And while the husband’s character is thinly drawn, Mirren’s performance makes up for it. She conveys an emotional complexity knotted with fear, suspicion, self-doubt and rage. She plays both the hunter and the hunted. Typically, the Hollywood treatment of a similar story would

men for great wads of cash, which he keeps stashed in a hole in the ground. Jack also cheats on the home front, commuting between a loving wife (Annabella Sciorra) and a compliant mistress Juliette Lewis).

Diabolical retribution arrives in the form of a double-crossing gangland dominatrix named Mona (Lena Olin), who disarms Jack in every sense of the word. As the plot careens through a giddy series of switchbacks, he proves to be no match for Mona, a cackling she-devil who, in one remarkable scene, attacks him from the back seat of the car he’s driving, strangling him into submission with her scissored legs.

Liberally splashed with blood, Romeo is Bleeding lives up to its title. But it is more fanciful than director Peter Medak’s previous two gangster movies, The Krays (1990) and Let Him Have It (1991), which were both based on harrowing true stories. Like those movies, however, Romeo explores the sexual pathology of guns and gangsterism. Jack has nightmares about women taking his gun—visions of being shackled to a bed while both Mona

and his wife aim revolvers at him. And as his bad dream becomes a reality, Mona rubs the salt of sexual humiliation into his wounds.

Olin brings breathtaking gusto to the role of Mona. With her appetite for voracious cruelty, the character breaks new ground in female villainy. And, as always, Medak’s images have a disturbing beauty. But with its cartoon-like violence, convoluted plot and overstated conceits, Romeo is Bleeding is a joke that wears thin—one cynically told at the expense of its characters.

China Moon involves another cop who walks both sides of the law and gets involved with a dangerous woman. But it stays within the Hollywood formula. Ed Harris plays Kyle, a homicide detective in a steamy Florida town who falls in love with Rachel (Madeleine Stowe), an unhappily married woman. Rachel has learned that her husband, Rupert (Charles Dance), is having an affair. He is an unsavory type with no redeeming features aside from money, a businessman who likes to slap her around. Rachel goes out and buys an illegal handgun, and before long she is asking her new boyfriend to help her dispose of the husband’s body. Kyle has to cover up the crime, which allows for a fascinating display of forensic housework. Then he investigates it with the help of his keenly inquistive partner, Lamar (Benicio Del Toro).

With its steamy southern setting and Spanish-moss tangle of murder and romance, the movie is reminiscent of Body Heat (1981), the bayou mystery in which William Hurt and Kathleen Turner locked libidos and played Who Do You Trust? But China Moon is Body Heat without the heat. And the fílm, a directorial debut by American cinematographer John Bailey, is more driven by plot than by character.

Stowe plays an ambiguous heroine—an abused wife and a killer with questionable motives. But even behind all the intrigue, for a femme fatale she is not very bright or interesting. Her character seems weakened by the attempt to make her sympathetic. Harris, on the other hand, carries the drama with an acutely observed portrayal of romantic obsession-few men would be so fastidious in cleaning up after their lovers.

Increasingly, women in the movies are picking up guns. In a few instances, notably Thelma and Louise (1991), they are showing a new bravado, with feminist overtones. But in movies like China Moon, a woman with a gun is just another stupid woman—with a gun. Hollywood is handing out weapons to women right and left; strong roles are still hard to come by.