|

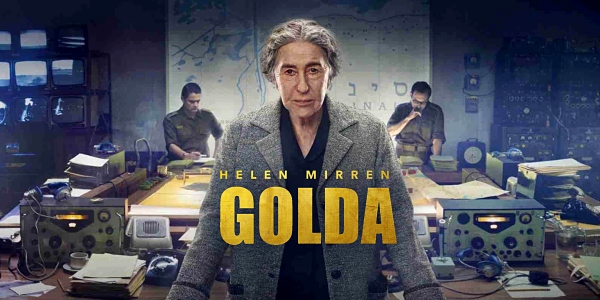

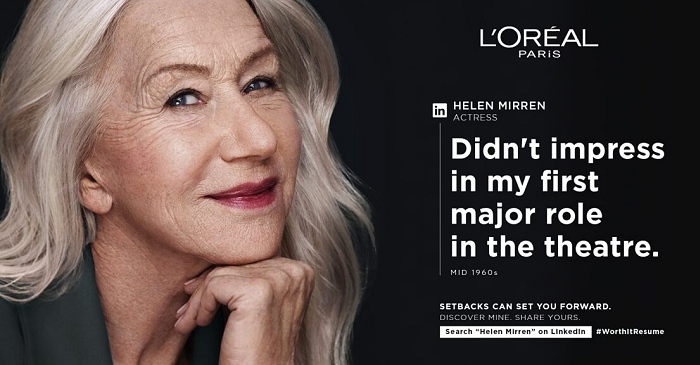

Welcome to The Helen Mirren Archives, your premiere web resource on the British actress. Best known for her performances with the Royal Shakespeare Company, "Prime

Suspect" and her Oscar-winning role in "The Queen", Helen Mirren is one of the world's most eminent actors today. This unofficial fansite provides you with all latest

news, photos and videos on her past and present projects. Enjoy your stay.

|

Celebrating

10 years

on the web

|

The critics hate ‘Antony and Cleopatra’ (with Helen Mirren and Alan Rickman) almost as much as they despised Peter O’Toole’s ‘Macbeth’ . But the actors still have to brave the audience, night after night after night.

When the National Theatre’s new Antony and Cleopatra opened recently, one critic referred to the courting couple, played by Alan Rickman and Helen Mirren, as “a pair of glumly non-mating pandas at London Zoo, coaxed to do their duty”. Others were equally damning. The performance was judged to be “rumpled, woebegone”, “thoroughly unengaging” and “downright lazy”

But if the critical hyperbole can be fun to read, it constitutes an intricate form of torture for the actors who have to tread the boards each night knowing that they have become the definitive barometer of bad. “That play has to run for a long, long time,” says Michael Bogdanov, artistic director of the English Shakespeare Company, “and the cast have to live with those notices. It’s very tough psychologically: they’re having to expose themselves to people they think have read all the criticism. Their friends will be avoiding eye contact, or being over-jokey.”

It is a common enough experience in the theatre. Despite threadbare audiences or poor reviews, actors are told that the show, however bad, simply must go on. Lysette Anthony, who plays the title role in the musical Jackie, has also suffered a critical grilling in recent weeks. The show was due to close last night after a run of only three weeks. “After bad reviews, you have to be fantastically professional,” she says. “You have to haul your butt out there and do the performance again and again and again, regardless.”

After the anticipation and excitement of rehearsals and opening, critical disdain or an abrupt closure come as a rude shock. Some people, such as the playwright Michael Frayn, try to overhaul the production. “You never really know that a project is bad until you’re in front of an audience,” he says. “With my 1991 play Look, Look, we all knew it was dead in the water on the first preview night. Until then, we were absolutely confident we were on to a winner. The audience is part of a play; you can control everything else, but it all changes when the audience arrives. I decided we had to make the thing work. I rewrote and rewrote, and the actors learnt new versions in 10 days.”

Given the notorious eggshell egos of actors, the shock of a harsh critical response must be particularly acute. Simon Gray is the author of Cell Mates, the play from which Stephen Fry walked out. “Of course actors become depressed,” he says. “But they do support each other, and there’s a lot of laughter, albeit gallows laughter, in the green room. It does depend if people knew it was going that way, whether they were already stoically resigned. But if they thought it would be a success they can go into shock, because the evidence of preview nights is so often contradicted by critics.” To the chagrin of many actors, it is no longer the practice of critics – as it was for the 19th century’s G H Lewis – to record the atmosphere in the house before demurring from or corroborating that reaction.

So the first recourse of a cast in crisis is usually defiance: to blame, or even in the case of Berkoff or Orton, to threaten the critics. This week, the actor Robert Lindsay used a question-and-answer session in Stratford-upon-Avon to denounce critics, and the “maulings” they dish out. “I think it’s going to get harder and harder if people don’t start treating actors in this country with respect,” he said.

Lysette Anthony expresses the same dismay. “We’ve been closed down by five or six grown men with an agenda. If they had spray-painted the theatre ‘Yanks Go Home’, it couldn’t have been more clear.” The indeterminacy of the run makes actors even more sensitive to critiques. “We were booked until the New Year and now, after only a few weeks, there are 60 people unemployed as of Monday.”

Stephen Fry has spoken of critics’ “vile, possessive impertinence”. Simon Callow once wrote of feeling “lobotomised” after reviews. “It’s depressing to spend so much time in contemplation of people for whom one has so little respect,” he says.

One production which has been teetering on closure, The Dead Monkey at the Whitehall, is even considering suing a hack from the Mirror who reviewed the play on GMTV without having seen it. Another critic, Robert Gore- Langton of the Express on Sunday, caused indignation among the cast: he gave the play a glowing review when it was on the fringe, only to write “It’s like watching a slab of marge in the microwave” when it transferred to the West End.

The result of such a critical slamming is always financial: the producers of The Dead Monkey, Alexa Hamilton and David Soul (who was once Hutch of Starsky and. . .) are now working for free, and tickets for Jackie have been literally given away outside the theatre for the past 10 days. Losses for Jackie are estimated at more than pounds 1m for the three-week run. The producer, Mark Schwartz, admits: “It’s a tremendous disappointment. But the theatre’s a strange thing. Jackie’s been a huge hit on Broadway and in Germany – as ber Jackie – but here the critics shut the door on us and nailed it closed.”

If there remains a solidarity and self-confidence amongst the cast and crew of a “flop”, it’s usually in the hope that they’re being too “avant garde”. Many an actor has been buoyed by the famous story of the critic Harold Hobson going to review Pinter’s The Birthday Party in 1958. When he arrived at the theatre, there were only five other people, one of them another Harold, the playwright himself. “There’s no explaining,” says Simon Gray, “why a good play is taken badly, or a bad one well.”

The unscrupulous choose to abandon ship as soon as they suspect it is sinking. The most legendary howler in theatrical history, Peter O’Toole’s Macbeth at the Old Vic in 1980, was publicly disowned by the artistic director of the Old Vic, Timothy West. He then had a very public spat with the director, Bryan Forbes, who defended his production in a first- night curtain speech.

Earlier this year, Nicola Hughes walked out on Bonnie Langford’s dreadful Sweet Charity days before it was due to open. (She chose to appear in Chicago instead.) Others make for the stage door during the performance itself. In 1995, Nicol Williamson apologised to the audience after a spotlight had missed him and left the stage; Daniel Day-Lewis, thinking he had seen the ghost of his father during Hamlet, did the same.

The alternative is the producer pulling the plug. Cameron Mackintosh’s Martin Guerre originally opened in July 1996, but was pulled off stage to be revised and reworked. The same happened to Mackintosh’s Moby Dick: A Whale of a Time! which – opening to disastrous reviews – ran in the West End for only four months. It later re-emerged on the Edinburgh fringe as Moby!

But the embarrassment of the Antony and Cleopatra cast is compounded for various reasons: in a bid to save money, the National no longer has plays in repertory in the Olivier, but allows productions to continue back-to-back. While this saves on the cost of, for example, scene changing, and allows the big earners to remain in situ, it means the performances are relentless, allowing little time to fine-tune or rework the things which are not working. Also, productions at subsidised theatres such as the National are not subject to the same pressure to succeed commercially, and so never – whatever the standards or sales – close early. Antony and Cleopatra will run until 3 December

Another reason for red faces, again tied to finances, is the importance of celebrity casting. (It is Simon Gray’s contention that some producers are now casting plays only once they have chosen their stars.) Celebrities are good for advance sales, and the Mirren-Rickman charisma meant that the play was sold out before its quality had been assessed. Now the cast play to what is, until the interval at least, a full house.

This strange hit/flop hybrid – a financially buoyant but artistically bankrupt production – is not a recent phenomenon. Peter O’Toole’s Macbeth also teamed up the Bard with celebrity. The production was called a “ketchup- drenched near-pantomime version” at the time, and yet – so keen was a gleeful public to witness such an epic failure – the theatre took record bookings. It is an old saying, but in the theatre there is no accounting for taste, only a taste for accounting.