|

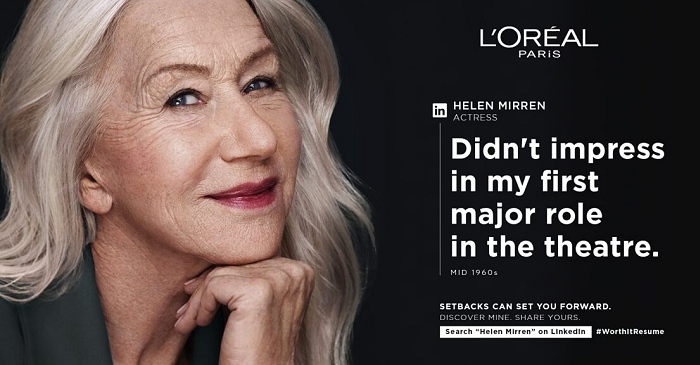

Welcome to The Helen Mirren Archives, your premiere web resource on the British actress. Best known for her performances with the Royal Shakespeare Company, "Prime

Suspect" and her Oscar-winning role in "The Queen", Helen Mirren is one of the world's most eminent actors today. This unofficial fansite provides you with all latest

news, photos and videos on her past and present projects. Enjoy your stay.

|

Celebrating

10 years

on the web

|

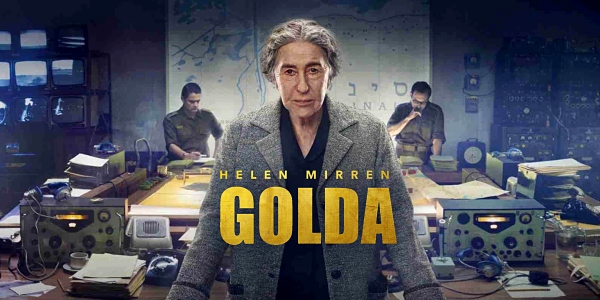

The legendary British actress reflects on her humble beginnings in London, becoming an American citizen and why she appreciates and encourages the debate about authenticity in casting sparked by her upcoming role as Golda Meir: “It’s a healthy discussion to have.”

It took the better part of two months to schedule an interview with Helen Mirren, the inaugural film star in the THR Icon series. Blame her punishing work schedule — the 76-year-old Oscar winner is coming off back-to-back-to-back productions, ranging from the British dramedy The Duke to F9: The Fast Saga (her third turn in the Fast & Furious franchise) to Shazam! Fury of the Gods, her first superhero movie, in which she plays the villain Hespera. When we finally nail down a time to talk, Mirren — speaking via video link from Italy in a home she shares with her husband, Oscar-winning American director-producer Taylor Hackford — has just finished shooting Guy Nattiv’s Golda, in which she plays Golda Meir, the prime minister of Israel during the Yom Kippur War.

An Oscar, Emmy, Tony and BAFTA Award winner, Mirren has had the equivalent of four or five ordinary careers. She was the youngest actress to be accepted into the Royal Shakespeare Company and helped lead the 1980s and 1990s revival of British cinema with roles in John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday (1980), Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) and Nicholas Hytner’s The Madness of King George (1994) — the latter securing Mirren her first of four Oscar nominations. Her primetime depiction of police detective Jane Tennison on ITV’s long-running Prime Suspect, a role that garnered Mirren six Emmy nominations and two trophies, was groundbreaking, and in the 2000s, following her performances in Robert Altman’s Gosford Park in 2001 (also Oscar-nominated) and her Oscar-winning turn as Elizabeth II in The Queen (2006), Mirren was finally elevated to “national treasure” status in Britain.

Then, well into her 60s, Mirren became an action movie star, first as an assassin lured out of retirement by Bruce Willis in RED and RED 2, then as Jason Statham’s East End gangster mum, Queenie, in the Fast & Furious films.

On Feb. 27, SAG-AFTRA will honor the actress with its highest tribute: the SAG Life Achievement Award for career and humanitarian accomplishments.

Endlessly curious, phenomenally talented and endowed with a work ethic that would shame a 20-something, Dame Helen Mirren has survived, thrived and transformed through six decades of a matchless career while still remaining indelibly herself.

Do you mind going way back, almost like a therapy session, to your childhood? You were born in London to an English mother and Russian father?

Yes. Well, Dad was born in Russia, but he came to England at the age of 2. On my father’s side, it was definitely an immigrant family. In those days, to have any kind of a foreign name in Britain was quite uncomfortable. He got it changed when I was about 10 from Mironoff to Mirren. So my dad was born in Russia, but my mum was London pure for who knows how many generations. A very old, London working-class family. Well, more of a trades family. You know, in England, we have all these different levels of class. Tradesmen is a particular class, and that was where my mum came from.

What are your strongest memories from growing up in London at that time?

Oh gosh. Well, I grew up in postwar Britain. So I remember rationing. We were not a wealthy family. Intellectually, I grew up in a very middle-class family, but financially it was [a] working-class [family]. My father eventually was a cab driver. Money was always very, very tight. Just the other day I was mentioning this. My husband always teases me because he says the British never take showers. But I was reminding him that, actually, we used to only be able to have a bath once a week because only once a week could we afford to light the boiler to heat the water to have a bath. So the whole family would have a bath on Fridays. My mum left school at 14, but my dad had an education. So intellectually, it was a very vibrant household.

Was it your dad who encouraged you to become an actress?

No. My parents were very against me becoming an actress. Understandably so because, you know, they came out of a depression followed by world war, and they had struggled financially, enormously. So they just wanted us to be financially secure. Financial security meant for us all to become teachers. And my sister did become a teacher. I, in fact, went to a teacher’s training college, but I very much wanted to become an actress. It was something that caught my imagination quite early in my life; I would say when I was about 12 or 13. I suddenly was exposed to the world of drama, basically through Shakespeare. I was very electrified by that. But my parents were very against it because they thought it was, financially, a disaster. It could well have been. I was very lucky that it wasn’t. But I do understand their attitude. Absolutely.

How did growing up that way influence your view of the world or your politics?

My father, though he came from a Russian aristocratic sort of family that had to escape from the Bolshevik Revolution, became — as a young, idealistic intellectual person in prewar London — a socialist. Maybe even a communist. In London, there was this famous moment called the Cable Street riots [in 1936], when the fascists, before the second World War, chose to walk through the Jewish quarter of the East End in London. There was a faction [that] stood up against them and tried to stop them on the march. My dad was very much a part of that faction. He was very anti-fascist. And, prewar, the anti-fascists were basically socialists or communists. I was brought up with a very lively political discussion, philosophical discussion. They never tried to influence us in any way. We weren’t beaten over the head with political dogma. Then I went to a Catholic girls school, which was the best non-fee-paying school in the neighborhood, and that was always a conflict for me — going to Catholic school with atheistic, socialist parents. They were great. They always wanted to open our minds, not close them.

You’ve played characters across the spectrum of nationality, politics and class. Is it more of a stretch for you to play the queen or Queenie [her character from F9]?

Well, Queenie is very close to me. She’s named after my Auntie Queenie — my mum was the 13th of 14 children. And the last eight of those children were all women. So I had a lot of aunts growing up in the East End of London. Working-class women. One was Queenie, and I based the character on her. But, you know, everyone is a human being. Everyone has their faults and their strengths, their vulnerabilities, their complexities and their fears, their ambitions, their cruelties and their generosity. It’s just a question of finding the human being in every character you play. So though my parents were republicans, they didn’t believe in monarchy. I’ve found myself, when I started researching the role, very admiring of the queen. I honestly never really thought about her before. To me, she was like Big Ben. She’d just always been there. The queen came to the throne when I was 7, I think. She’s been there for my whole life. I didn’t really take any note of her until I started having to research her as a person, as a human being. Then I found myself finding a huge admiration for her, and respect.

Is it mutual? Do you know if the queen has seen the film and what she thought of it?

I don’t know. At the time, it had never been done before, playing the queen. It was quite nerve-racking because I didn’t know — no one knew — how the public would receive it, let alone the establishment in Britain. But I got the sense that it had been seen and that it had been appreciated. I’ve never heard directly, and I never will. Of course, since my performance [there have] been many others [to play the queen]. I think Claire [Foy] and Olivia [Colman] on The Crown have carried it on and been absolutely fantastic.

Do you need that kind of identification or empathy with the character? What was it like with Golda Meir, whom you play in Golda?

Yes. I don’t think I could take a role if I couldn’t empathize with the character. I admire actors who can. Maybe our job as actors is to find the humanity in the character. But to play a real monster I think would be very, very difficult. With all the roles I take on, I feel an affinity with the character. Or maybe an understanding. Of course, if they’re real-life characters, you start searching, researching and trying to find the element in this person, this character, that you can identify with. It’s difficult to play Catherine the Great because there’s nothing in my life remotely equivalent to the life that she led. But you can always find little, often funny little elements that you can identify with or, if not identify with, understand. You go, “Oh, I see. I understand now.”

What were those moments for Golda Meir?

You know, the thing with Golda, as with the queen, was I’m playing them at a very specific moment in their lives. For Golda, it’s during the Yom Kippur War, which was a very difficult and very traumatic moment for her. So obviously that, on top of who she is, influences the performance. But, funny enough, I’ve found Golda and the queen to have a lot in common. Weirdly, there’s a similar single-mindedness and an absolute total, total dedication to the job at hand. Golda was an absolutely extraordinary person. I didn’t really know much about her before, but as I researched her, as usual my respect for her grew and grew and grew. Of course there are faults. Golda had faults. People like that who are very driven, certain things in their lives have to become, if you like, one dimensional, because without that attitude, you can’t achieve what you need to achieve. Golda could be very rigid in many ways. But she was an absolutely extraordinary person, with extraordinary strength and absolute commitment. We have at least one element in common, which was we both worked on a kibbutz. I worked on a kibbutz for a very short period, a long time ago, in the late 1960s. So I did at least have that experience.

There has been a lot of talk and criticism in the British media about you playing Golda despite not being Jewish. What do you think about this discussion and the broader idea of authenticity in terms of casting?

I’m really glad that the discussion is out there. It’s a very important discussion to have. In fact, when I was meeting with the Israeli director of Golda [Nattiv], I said: “You know, I’m not Jewish, so if that changes your mind about casting me in this role, I understand and I will step away, no hard feelings, because I think it might become an issue.” His response was that he wanted me to play that role. And that was it. So I had thought about that beforehand. But, you know, it’s a fascinating discussion, and I absolutely appreciate the explosion of understanding of what casting can or should be. You know, [in Britain] we have a Black actor called Adrian Lester, who played Henry V, brilliantly, and very, very successfully. Well, Henry V definitely wasn’t Black. But it doesn’t mean that a Black actor can’t be absolutely brilliant and show us something, reveal something about the role of history, about the character that maybe one hadn’t thought of before. I love casting against type, against gender, against race, for the whole thing to be out there. But, at the same time, I absolutely understand a deaf actor saying: “I’m a deaf actor, I’m an actor, if there’s a deaf role, at least give me the chance to play it.” I absolutely understand that. We’re in a world where all these questions are up in the air, but I think it’s a healthy discussion to have.

Looking back on your career, are there any roles that you regret taking? Or are there roles you didn’t get that you would have loved to play?

I don’t think so. I mean, I’m sure I’ve made many mistakes, but mistakes are part of life. You know, you carry on. Some things I’ve done have been far more successful than other things. Certainly, there are roles I wish I had done that I was asked to do but turned down. But I’m not going to name those.

I’ve heard you were up for two roles that Meryl Streep ended up getting: The French Lieutenant’s Woman and The Devil Wears Prada.

No, no, no, never. I didn’t have a chance with those. Maybe someone mentioned my name at one point — but without me knowing it. The only thing Meryl did tell me was she based her hairdo in The Devil Wears Prada on my hair. That’s all I can claim.

You have had several distinct periods in your career. You started in theater, then did British TV, then art house movies.

Well, at the time, in the 1970s, British film was kind of nasty. It wasn’t very good. It was said — and it was true — that British film was alive and living on television. Many of the film directors who became very successful — like Alan Parker and Peter Greenaway — started working in television. I did quite a few major roles on television through the ’70s. That was sort of my training for working on film. But most of that’s gone. The BBC, because it wanted to use the tapes again, wiped everything. Can you believe it? They lost so much great work. Now the opposite is true: You can’t escape from anything you’ve done. It’s out there forever. I had a tough time tracking down a lot of your older work, but I did manage to watch that extraordinary interview you did with Michael Parkinson in 1975. [The BBC host condescendingly asked Mirren whether her “physical attributes” detracted from her abilities as an actress.] It’s shocking to watch now; it almost seems like a comedy sketch, it’s so outrageous.

Like an SNL sketch, yes.

It illustrates how sexualized you were early in your career.

Oh, absolutely. I used to think of it as a sort of, a rather uncomfortable backpack that I was having to carry with me. But it was something I realized quite early on that I just had to deal with, had to accept and sort of carry on regardless. To not allow it to affect me. It wasn’t altogether detrimental — it was valuable in some ways. But, at the same time, it wasn’t really me. It was me in the sense that I looked the way I looked, and some people saw that in me.

As I got older, I started to quite enjoy it, to play with my image. But when I was younger, it was really a pain in the butt, quite honestly. But I always said to myself: It’s the work that counts. I think that’s partly why, early in my career, I really concentrated on becoming, for lack of a better word, a classical actress. It’s the work that counts, so keep doing that sort of difficult, challenging work, and this other thing will hopefully drop away.

Now you seem to almost enjoy playing with that image.

Yes. Now, absolutely. I love to dress up — it’s fine. Now it’s absolutely fine. Because, you know, I’m much, much, much older. When you’re a young woman, especially in that era, being sexualized was the opposite of what I wanted. That or the opposite: “Oh, you’re not sexy at all.” The whole attitude was just paralyzing. And absolutely enraging.

Do you think it’s different for young actresses now?

It’s absolutely different now. There are elements of it still, but I think — and I might be wrong about this — but I think young women have claimed that territory, their sexuality, for themselves. They’ve got the chins up about it, they don’t have to substitute for it or feel embarrassed about it. Sexuality used to be disempowering. Now I think maybe it’s empowering.

When it comes to the roles you’ve played, are there any you feel really capture an aspect of yourself that you rarely get to show?

It’s a good question. I don’t think so. I think the characters that I feel closest to, in a way, are the ones that have been furthest from me as a person because I could really enter the psychology of someone very different from myself. I played Ayn Rand for Showtime [in 1999’s The Passion of Ayn Rand], and I found her an absolutely fascinating character to investigate. Weirdly, again, a bit like Golda or the queen. This amazing, hugely intellectual but so single-minded [woman] became emotionally stupid. That’s not the right way to put it, but she couldn’t handle normal human emotions. Like falling in love. She was absolutely hopeless. I’ve found that contradiction absolutely fascinating. But a character whose personality and politics couldn’t be further away from my own.

Speaking of politics, you recently became an American citizen and voted in your first election, in 2020.

I was very moved; I cried actually when I became an American citizen. It was a very moving moment. I’m a dual citizen now. I wouldn’t have been able to give up my British citizenship.

You’ve been married to an American for many years already. What pushed you to become a citizen?

I was in New York doing a play on 9/11. I actually saw the second tower come down. I was living quite far downtown, and I was going to rehearsal — we literally were about to open the next week — and the car arrived, I got in the car and looked out the window and saw the second tower come down. I went and I bought an American flag and I put it outside my window. I just thought: “If I’m on any side of this fence, I know which side I’m on.” I don’t believe in nationalism. I don’t like British nationalism, or American or French or German or Italian or, you know, Saudi Arabian. I don’t like any nationalism. But there are moments when you have to say which side you’re on.

Is it easier at the moment to be an American citizen than a British one?

They’re both very challenging at the moment, but I guess that was always the case. I certainly would have more respect for the American B [Biden] than the British B [Boris Johnson] at the moment.

What appealed to you about doing action movies like RED and F9?

Well, there’s no real difference to the work. The periphery is different, you know, the number of trailers or the sets or the amount of time you’ve got to shoot a scene. But, fundamentally, it’s exactly the same thing. But I love the special effects world. And the stunt world. I really believe stuntpeople should be nominated for Oscars. They’ve become such an intrinsic part of filmmaking now. You look at these big action movies, and it’s 75 percent stunts, really. I love working and watching the art, the craftsmanship and the expertise of these people. The whole digital side of things, the special effects, is just extraordinary. Every time I go on set, the technology has advanced to another level.

Is it true you asked Vin Diesel if you could be in the Fast & Furious movies?

I didn’t ask, I begged! I think I was at some function, and he was there, and I got introduced to him. And I was shameless: “Oh God, I’d just love to be in one of your movies! Please let me be in it.” And then Vin, with that beautiful, deep voice of his, said: “I’ll see what I can do.” And he did it for me. He found this great little role for me, which was perfect. I’d just never done anything like that before — one of those big, big movies. And, in my vanity, I just loved driving and really wanted to do my own driving in a fast car.

What advice would you give a young actress just coming up in the industry?

I don’t know. It’s tough. I would just say, try to mix it up and take every opportunity that comes your way. Try to make the best of whatever comes your way. My mantra is, “Be on time and don’t be an asshole.” That’s fundamentally my attitude in life.

Interview edited for length and clarity.