|

Welcome to The Helen Mirren Archives, your premiere web resource on the British actress. Best known for her performances with the Royal Shakespeare Company, "Prime

Suspect" and her Oscar-winning role in "The Queen", Helen Mirren is one of the world's most eminent actors today. This unofficial fansite provides you with all latest

news, photos and videos on her past and present projects. Enjoy your stay.

|

Celebrating

10 years

on the web

|

Tags

|

Dame Helen Mirren greets me enthusiastically on the phone from New York City after a day of promotion for her latest thriller, The Good Liar, in anticipation of digitally featuring as Flaunt’s first Annual Icon. I’m over 3000 miles away in Manchester, England. The first thing Mirren wants to talk about is not her current film, nor her other high-profile role in HBO’s Catherine the Great which is currently airing, but Manchester—the city where she arrived as a young actress in 1965. Mirren eventually returned to the city 26-years-later for her life-changing, BAFTA and Emmy winning performance as Jane Tennison in Prime Suspect. “I owe Manchester a great deal,” Mirren says fondly. “I had my very first professional job in Manchester and of course Prime Suspect came out of Manchester and it was filmed there too. I hold it very close to my heart.”

For a time in the late 1960s, Manchester was a home-away-from-home for Mirren as she appeared in several Braham Murray-directed plays at the city’s Century Theatre. Her initial route in came via the UK’s Youth Theatre scheme where those without the means to afford astronomical drama school fees were supported into a career in the arts via a vocational route. “I was dying to go to RADA but I couldn’t,” Mirren says, sadly. Yet her talents were quickly spotted: months later she was hired by the Royal Shakespeare Company where she soon became one of the company’s most acclaimed actors. Eventually, Mirren appeared on prime-time British television where her gritty portrayal of the ambitious Tennison—one of the first female detective chief inspectors of the metropolitan police—changed her career forever: it changed the face of women on screen forever too. “I wish that I’d have had your experience when I was in my teens,” Mirren tells me, when I tell her Jane Tennison was the first female character I’d watched on television in charge of a group of men. For Mirren, no such figure existed. “Jane Tennison was the first,” Mirren says, recalling how Tennison stood apart from the two-dimensional roles women were usually offered on television in that era. She can remember just two other female-fronted police shows on screen from her youth: the saccharine Juliet Bravo and the relatively safe Cagney and Lacey. Prime Suspect, conversely, was far from safe or saccharine. It highlighted, often in stark, brutal detail, the detrimental personal costs a woman in a high-profile, male-dominated workplace was forced to endure on a daily basis.

“Her ambition and her self-interest and the fact she knew she was better than most of the people—most of the men—around her. The way she had to be quite ruthless,” Mirren beams, recalling Tennison with pride. “The way her relationships with her parents, her family, her boyfriend all got pushed to one side for her job. There hadn’t been anything like that.” British viewers accustomed to safe Sunday night television shows were shocked at seeing a woman “behave like a man,” as Mirren puts it. “She wasn’t self-effacing, and she wasn’t ‘long-suffering’ either. I hate that word,” Mirren balks. “I loathe it. You rarely hear that word applied to a man but very, very often to a woman. I’ve played a few of those characters and Jane Tennison was absolutely not long-suffering and she wasn’t self-effacing. She was real and she was wonderful.” In her latest film, The Good Liar, adapted from a Nicholas Searle novel by Jeffrey Hatcher, Mirren plays another strong woman, Betty McLeish—a retired teacher in the suburbs who’s survived numerous adversities and looking for companionship in the golden years of her life. Through the internet, Betty meets Roy Courtnay (played by Sir Ian McKellen), a charmer on the outside, but a conniving conman and fraud beneath his winsome smile. As the two titans of theater engage with one another, secrets unravel, and histories are unearthed, “twists and turns,” as Mirren teases. In one scene, Betty is assumed to be a retired schoolteacher by Roy. It’s left to Betty’s grandson, Steven (played by Russell Tovey)—who openly expresses to his grandmother his consternation with Roy’s disposition—to correct him: Betty was an academic and did, in fact, teach and lecture at Oxford University. Roy stares at Betty in disbelief before a shocked, surprised half-smile passes his face: it’s not dissimilar to the moment in Prime Suspect where a room full of male officers react when they realize Tennison is their new boss. Mirren says the shock for characters like Roy comes from living in a world where women’s roles are still not equal to men’s—although she is hopeful things are starting to move in the right direction.

“I’ve always said, even when I was a young woman, I said I don’t worry about the variety of roles available for women on screen. I worry about roles for women in real life. As we see women enter into major roles in real life, drama will follow. There are still not enough roles yet, but they’re coming. The unfairness and the prejudice of the lack of roles for women has always driven me crazy, it’s enraging. But things are slowly changing.” There’s regret in Mirren’s voice. “I do think in the last five years it’s been such a huge change and I would love to be seventeen now in this environment. And I’m very jealous. I’m very jealous of the girls who are seventeen now. I am very jealous of the world they are stepping into, it’s so much more woke,” she laughs. “The world was so deeply asleep when I was seventeen and I was fighting a losing battle.” Her words crush, not least because of the frustration the 74-year-old expresses at the pace of change in the industry. She wonders about all those actors who didn’t get through. It’s one of the reasons, she explains, why she thinks it has taken decades for her to appear on screen together with her peer, Sir Ian McKellen. While the two have shared a stage together on Broadway in 2001, The Good Liar is their first-time side-by-side on screen. It’s telling for Mirren. “No, our paths just didn’t cross but I think that’s a lot to do with the paucity of women’s roles. It’s extraordinary to me when you say this to male actors—they really don’t get it or maybe don’t want to confess to it, don’t want to recognize it. For every thirty male actors in a Shakespeare play, there are two women and it’s still incredibly unbalanced.”

A cursory glance at reviews of Mirren’s early performances or at footage from her television interviews from the sixties and seventies, reveals the dire misogyny she faced. Reviews would concentrate on her body and looks; interviewers would focus on the amount of sex her characters had. One early review in The Guardian dubbed her ‘The Sex Queen of Stratford’; interviewer Michael Parkinson asked Mirren repeatedly in 1975 about her “physical attributes” and roles involving “nudity”, despite her clear upset and attempts to shift the conversation back to her career. The interview recently went viral after being unearthed and viewed through a horrified #MeToo lens. “I mean after that Parkinson interview, I was the one who got the shit,” Mirren says. “He didn’t. I got the shit. I got the shit for being argumentative.” The interview makes for a difficult watch. At the time, Mirren was at the height of her powers at the RSC. “I don’t want to diss Michael, but he did blow it that once,” Mirren laughs, “because, you know, he didn’t know any different. He never saw it. I mentioned it to him again years later and he never saw what was wrong with it. He never could quite grasp it.” Mirren’s tone suggests she’s met many men who couldn’t quite grasp such issues in her extensive, 50-year-career. She simply sighs.

Mirren tells me it’s why taking on the role of Catherine the Great now is so satisfying. A woman maligned in history after her story was re-written and scandalized by men, Mirren’s extensive research of the leader (she fires off the name of a dozen academic biographies and all of Catherine’s handwritten letters and diaries that she’s read in her preparation for the role) suggests that we’re finally going to see the real Catherine via Mirren’s new HBO and Sky Atlantic mini-series. The role also sees her returning to her roots once more as she’s reunited with Philip Martin, who won an Emmy for directing Mirren in Prime Suspect. Now, he’s written her latest script. Like Jane Tennison, Mirren says, Catherine lived life on her own terms at a time when men found such behavior threatening. “If you behaved the way a man did as a woman, then insults and assumptions were thrown at you that would simply never be thrown at a man,” she says of Catherine. “It kills me because reading her letters and looking at her achievements, she was an extraordinary woman and very sweet. She was funny and incredibly smart but didn’t parade her smartness. She could be ruthless when she needed to be but that was never her driving instinct. Her driving instinct was forgiveness, kindness, humor, and generosity.” Mirren’s passion for the character is palpable, so too is her thirst for a good “barnstorming role,” as she terms it, fifty years into her career. Her meticulous, conscientious preparation for the role illustrates the lengths the actress goes to in empathizing with the characters she plays—a skill which has seen her achieve an Oscar, 4 BAFTAs, a BAFTA fellowship, 4 Emmys, 3 Golden Globes, a Tony, and a Laurence Oliver Award—to name a mere few (there are many, many, more). Having played the most high-profile of regal roles—Elizabeth I and II included, Mirren says when preparing for her role as Catherine the Great, she drew as much as those quiet, “long-suffering” characters from her early days in Manchester to influence her portrayal as much as the royal ones. She never, she says, forgets her “roots.”

“I don’t like to bang on about it. People say: ‘oh you’ve played all these queens.’ I have played the odd queen and obviously The Queen but especially with Shakespeare, that comes with the territory to a certain extent. But I’ve also played a lot of other characters too. Jane Tennison [is as much] a leader as Catherine. I’ve played housekeepers and cleaners. What I try to do with all these people, no matter what their status, is to find the simple humility in them. I humanize them and make them more believable and understandable.” Catherine, she tells me, came out of history as a “sex-crazed creature” because she’d had multiple lovers—a normal occurrence for her male counterparts. Ridiculous “rumors and smears” were spread, Mirren explains, as she zips through a potted, knowledgeable history of the leader. “The horse!” she howls, when she recounts the tale of her enemies writing that Catherine “loved” equine sex. Mirren says the real truth about Catherine becomes evident when you look at her life through a modern feminist lens. “She was a prodigious letter writer. Her language is so accessible. The sweetness is there, the humor and wit—which is slightly gossipy in tone—but at the same time, she was very inquiring and very intellectual.” Mirren read all of Catherine’s letters to Voltaire as part of her research. “She was very interested by all the liberal ideas coming out of France,” Mirren explains of the leader, who stood up to one of the largest peasant revolts in Russian history. Yet during her research, Mirren was frustrated when feminists wouldn’t ask her about any of the professional side to Catherine, only her sexual side—or what the deal was with the horse. “I was like ‘come on! This is one of the greatest women in history! You are a feminist, you should be at least educated about her and know the truth of her, one of the greatest rulers ever in the history of mankind.”

“I had to think like a guy when playing her,” Mirren reveals. “I had to think like a man, thinking society is not going to attack me for this. I can do this, I am allowed. There’s going to be no approbation about my behavior here. I don’t have to be secret. I had to think like a guy in the sense that there is going to be absolutely no approbation for my behavior. Of course, history did that for Catherine. History, written by men, was the one that threw the approbation at her…I realized that actually, even in our present day, we’re still coming out of the Victorian age to a certain extent,” Mirren says, when she hears some of the views on Catherine. Throughout her professional life, Mirren has challenged for equality—both as a feminist and as a socialist and her sense of justice is fierce. Mirren grew up in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, with her brother and sister, the daughter of a Russian immigrant father and a working-class mother. Mirren couldn’t afford to pay drama school fees and instead looked to the Youth Theatre system for help—a system which has now been reduced significantly in the UK as a result of government cuts to arts funding. Mirren’s anger is palpable. “It absolutely kills me, it kills me that theatre has gone back to what it was in the 1950s,” Mirren says. “When I started, it was a private club for posh kids. There were the ones who get through, via accident or luck. But my god, it’s so much easier if you had financial backing in those first few years of your professional life as an actor. The way in for me was the youth theatre. There’s this little door in that wall that was secretly opened for people like me to go through It was where working-class kids could go and experience theatre. It was a great, great help for me. Looking at that world, when you’re outside of it, I mean really outside of it—so no family members, no financial connections, it’s like looking at the Great Wall of China or something. You’re never going to get over it.”

Mirren’s parents didn’t see acting as a viable career, something she initially countered by training to be a teacher at vocational college whilst moonlighting in theatre at every opportunity. “I spent three years training to be a teacher full in the knowledge that I did not want to be a teacher and that I would be a useless teacher if I eventually became a teacher. The ignorant foolishness of youth,” Mirren laughs. “My mum and dad were certainly economically in the working class and teaching was seen as a safety net. It was a case of ‘Oh don’t be ridiculous, of course you can’t be an actress. That’s stupid.’ Of course, they were absolutely right: I had no argument with them whatsoever. My [life] could have easily gone pear-shaped and I could have been a teacher. I would have found a way to be a good teacher I hope,” she reflects. It was only well into her career that Mirren was invited to join the board of RADA over 25 years ago—the drama school she so desperately wanted to attend. What she found, however, horrified her. “I was invited to be on the board of RADA over 25 years ago. I’d never been to RADA and as a young actor, I was dying to go to RADA. But I couldn’t. I was invited to be on the board there and I thought it would be great. There was an older gentleman on the board. We were discussing what we could do to bring more POC, people of all races into RADA. The board member, who Mirren doesn’t name, replied: “well, there aren’t the roles for them out there, are there?” Mirren was livid. “I retired from the board immediately at that point,” she reveals. “Literally those words came out of his mouth. I did fight it out. He was an old, established member of the board and I said I didn’t want to be a part of it anymore…I didn’t get up and storm out, but I instead retired immediately.” The new climate has given Mirren hope that incidents like this will become a thing of the past. “There’s been a wonderful, huge and overdue sea change which is exciting. The future looks a lot brighter than the past, put it that way.” Mirren adds: “I’m so excited by the change that’s happened. I’m so thrilled, not just for women but for all gendered people, all races of people…there are major moves afoot.”

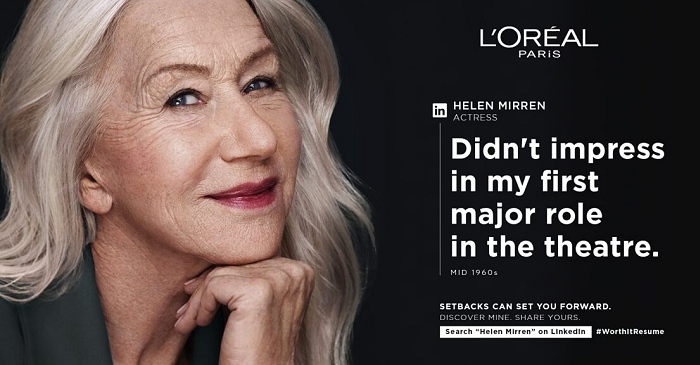

Mirren has always been an advocate for “realistic representations” of women on screens. As an older woman called up for the L’Oréal campaign—amongst others—Mirren insists that her photographs weren’t altered to make her look younger. She tells me she’s a fan of Dove’s advertising scheme, which sees real women fronting beauty campaigns. In a world where digital de-aging is now the talk of Hollywood, does Mirren feel it will bring more pressure to women trying to remain youthful? “You know, a lot of film, in particular, is fantasy, and people want to engage in fantasy,” Mirren begins. “It’s all a dream. That’s not our real lives, is it? I love seeing beauty, I love seeing beautiful images and the artistry of it all.” What “drives her crazy” though, she says, is unrealistic representations of women on screen. We laugh about the example of a 24-year-old female surgeon in an “eminent job” on screen, when in real life the woman wouldn’t have yet graduated. Mirren says despite such howlers, shift is happening. “You look at the incredible variety of roles for women now that are available on the screen, things are changing…You can watch a film now with a female President of the United States and people don’t sneer at the concept. Twenty-years-ago, people said that wouldn’t happen. More women are entering into the public sphere, in the worlds of science, in the worlds of politics and the media. They’re coming. Not enough, but they’re coming. The more the roles are coming along in the real world, the more they will be reflected in our movies. I don’t want to see a twenty-two-year-old as a surgeon though,” Mirren laughs. “But change is finally coming. I feel hopeful.”

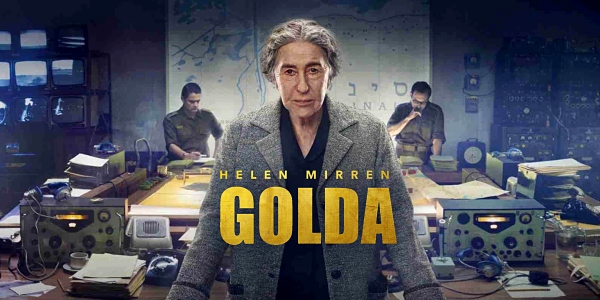

Available on home video Directed by Academy Award winner Guy Nattiv, Helen Mirren portrays the responsibilities and decisions that Golda Meir faced during Israel's

Yom Kippur War in 1973 |

|

Releases October 04, 2024 (USA) Feature film directed by Marc Forster | |

|

In pre-production Season 2 created by Taylor Sheridan |

|

|

Announced Feature film directed by Anton Corbijn |

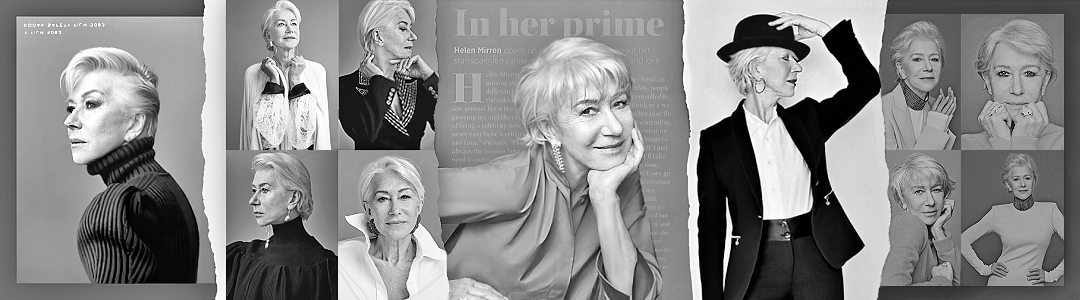

Mindfood Magazine (New Zealand) March 2024 |

Vanity Fair (Italy) December 29, 2023 |

Posted on April 11th, 2024

|

Posted on March 29th, 2024

|

Posted on March 19th, 2024

|

Posted on March 7th, 2024

|

Posted on February 16th, 2024

|