|

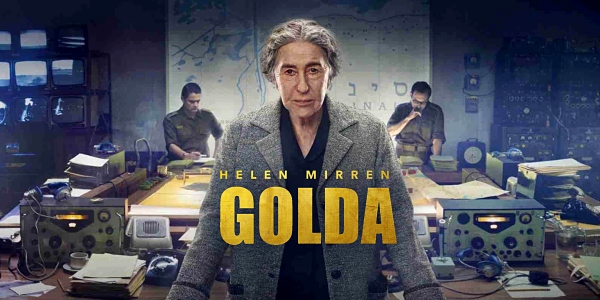

Welcome to The Helen Mirren Archives, your premiere web resource on the British actress. Best known for her performances with the Royal Shakespeare Company, "Prime

Suspect" and her Oscar-winning role in "The Queen", Helen Mirren is one of the world's most eminent actors today. This unofficial fansite provides you with all latest

news, photos and videos on her past and present projects. Enjoy your stay.

|

Celebrating

10 years

on the web

|

Helen Mirren loves to be naked, and believes that acting is more about taking off disguises than putting them on – but, she says, she hates to strip for the camera. On the eve of her latest performance in the West End, she reveals herself to Nigel Farndale

THE sticky heat of the afternoon is lifted by a cool dusk as Helen Mirren and I walk from her flat overlooking Battersea Park to a pub around the corner. ‘I don’t mean to be rude,’ she says in a measured voice. ‘But I probably won’t get around to reading your article. So write whatever you like. I really won’t mind. People take themselves far too seriously, don’t you think?’ To be honest, I’ve always been a bit neutral on the subject of Helen Mirren. She is electrifying as an actress, of course. Right up there with Dames Peggy, Diana and Maggie. But I’ve never understood why everyone goes on so about her sex appeal. Is it because she seems so willing to take her clothes off in the name of art? Now I begin to see why people make such a fuss. Helen Mirren is cool. And cool is, for want of a better word, sexy. A bottle of sancerre arrives, a drop is poured into a glass for us to taste, and Mirren hands it to me. I sip and nod approvingly. She then takes the glass back and, to my surprise, finishes it. She looks pretty cool, too: comfortable in her skin; not as tall as you would imagine but with softer, more fragile features. Her eyes seem more grey than blue, and her fine, shoulder-length hair is blonde but silvering at the roots (she’s 54). She is wearing a black skirt and a powder-blue cardigan, and when she leans forward, propping the side of her head up on her hand as she talks, I can’t help noticing that she is wearing a red bra. Helen Mirren has starred in 20 films. In some, such as The Madness of King George (1995), for which she won an Oscar nomination, she didn’t appear naked. In many – notably Caligula (1979) and The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989) – she did.

Is she an exhibitionist? Or just too cool to care? ‘I’m a naturist at heart,’ she says, taking a sip of wine. ‘I love being on beaches where everyone is naked. Ugly young people, beautiful old people, whatever. It’s so unsexual and so liberating. I hate the British attitude to public nudity. The sniggering Carry on mentality. So hypocritical, so uptight, so f-ed up. Such a manufactured scandal. But do I enjoy taking my clothes off on set? Absolutely not. It’s horrible. I do it because it’s part of my job and because I know it titillates and gets bums on seats. I’m not beautiful naked, and when there are 150 clothed people staring at me in a studio, I feel very self-conscious. It’s a form of torture. The only way to get through it is to blank everyone out and imagine that you and the naked actor you are with are Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.’ She grimaces. ‘I remember having to walk down a stairway naked in Ken Russell’s Savage Messiah. I was dreading that scene. I even considered jumping off my trailer in order to break my legs, so that I wouldn’t have to go through with it. Afterwards I felt so unhappy, so mortified, so embarrassed.’ Mirren refills her glass and says that she is enjoying drinking wine again. She has just returned from Ecuador where her husband, Taylor Hackford, the Hollywood director best known for An Officer and a Gentleman, is working on location. The high altitude there made her feel sick, especially if she drank wine. She has returned to London to star in Tennessee Williams’s Orpheus Descending at the Donmar Warehouse. ‘I went straight into rehearsal off the plane and I hadn’t even done a read-through. I’m terrible like that. I always do everything at the last minute.

I was like that at school, doing my revision on the morning of the exam.’ The play, which is directed by Nicholas Hytner, is set in Mississippi. Mirren plays a lonely shopkeeper’s wife condemned to a loveless marriage until a mysterious stranger, played by Stuart Townsend, ‘descends’ into town to snatch her back from the depths of hell. She tries her Deep South accent out on me. ‘Being married to an American don’t help at all, honey, because he’s Californian, see?’ (The accent sounds convincing to me.) She and Hackford have several homes but mostly they divide their time between London and Los Angeles, and not always at the same time. ‘I would feel like an idiot if I came back to England with an American accent,’ Mirren says. ‘I’ve consciously avoided picking one up. Yet there is an urge to fit in. When I’m in the States, I hate having an English accent.’ The couple married in 1997, after 13 years together. Mirren had always dismissed the idea of marriage, so what changed? ‘We’d been together so long it felt like a marriage anyway. But it was more for practical reasons than romantic. We realised that, as likely as not, we would still be together when I died, or he died, so there were legal and financial considerations. I love being married and I wear a wedding ring, which I didn’t think I would. But I’m not hugely into the idea of marriage. I didn’t want it to change my relationship, and it has, which is a bit worrying. There’s a territorial thing. On both sides. Square footage. Battersea is more my space and LA is more his. When I went there for the first time, I felt I had no identity. I was living in luxury but was unutterably miserable. I didn’t feel it was my house because I hadn’t bought it. I won’t even buy towels with his money. I’ve always felt a great need to have economic independence. I think it’s to do with my upbringing.

There was no money in my family.’ Mirren’s father, Basil Mironoff, was a taxi driver in Southend-on-Sea. He arrived in England from Russia when he was two. His father, a Tsarist colonel, had come over to negotiate an arms deal just before the 1917 revolution and never went back. ‘We weren’t cultural in the sense of having books or a record player or a radio or a television in the house, but we did have conversation. Lots of it. Mostly about politics. My father was very left-wing, a Communist in fact. He used to go on the anti-Mosley marches in the East End.’ Ilyena Lydia Mironoff, as she then was, went to a Catholic grammar school but, like her parents, she remained an atheist. ‘One of the last things my mother said to me before she died was, “For God’s sake, don’t get religious on me!” She didn’t hear the contradiction in that.’ Mirren’s mother, Kit, the daughter of an East End butcher and horse dealer, died four years ago at the age of 87. ‘I watched her die over six months. She had a series of strokes that took her further and further away from life. It was the perfect length of time to focus your thoughts. She didn’t mind the idea of dying. She loved it, in fact. She’d had enough. It was time. She didn’t necessarily articulate it that clearly, because she’d had a stroke, but I had a sense of how she felt. She donated her body to science. There was no funeral or coffin, she was just…’ Mirren clicks her fingers. ‘Gone.’ Silence. She looks away. Wipes a tear. ‘I don’t mean to cry, it’s just… What I found was that I didn’t want to let go of her history. Her life was my connection to the world before the Second World War. Towards the end I would ask her for her stories, even when I had heard them before. How she got bombed. So brave. And we are so spoilt. Being working-class in the Thirties in London was no f-ing joke.’

Did Mirren feel that she was betraying her roots by shedding her accent? ‘No. My mother had learnt to talk properly. She was very strict about the way we talked when we were growing up. She was obsessed with us not having accents or bad grammar. The biggest row my parents ever had was when my dad got a job in the North of England as a driving examiner. I must have been about ten, and I remember Mum saying that she didn’t want us growing up with northern accents. She felt it was beneath her. She scraped enough money together for my sister [Katherine] and me to have elocution lessons, but not my brother [Peter], for some reason.’ Was there anything in her childhood that put her off wanting to have children herself? ‘Not really. I think a lot of women are like me actually. Often they have to keep their mouths zipped about not wanting children because it’s not acceptable, not natural. I don’t think my mother was a natural mother. I’m pleased she had me, but she didn’t hugely enjoy being a mother. So maybe that influenced me. I think she just didn’t have the maternal instinct. Like Queen Victoria. I haven’t undergone some huge psychological investigation into this, it’s just as clear as day to me that it’s not what I want. I don’t crave children.’ After a brief spell working in Southend-on-Sea as a ‘blagger’ – luring customers on to fairground rides – Mirren went to teacher-training college. But at 19 she gave it up to join the National Youth Theatre, graduating to the RSC where she remained – on and off – for the next 15 years, turning in a celebrated Cleopatra and becoming known as the ‘Sex Queen of Stratford’.

The nickname came about partly because of her sultry presence on stage, partly because she made no secret of the string of lovers she had off stage. For a while she lived in an aristocratic commune in Wiltshire, a large country house run by Lady Sarah Ponsonby and Roddy Llewellyn and occasionally visited by Princess Margaret. Mirren described it as being ‘all bongo drums and five-skin spliffs’. On her right hand, at the base of her thumb, there is a tattoo from this period. It depicts two inverted Vs, an American Indian peace symbol. She had it done in 1973, while trekking around North America and Africa, performing experimental theatre with Peter Brook. ‘Despite the friends I still have from the commune,’ Mirren says with a flick of her hair, ‘I feel the counter-culture passed me by. Even while I was at the commune I was working at Stratford because I wanted to become a great actress. I was never a drop-out.’ This said, she thinks she may have inherited a bohemian attitude from her father. ‘He was a sort of bohemian in the Fifties. His taxi rank was on the King’s Road and he used to love wearing corduroy and hanging out in jazz clubs. I think I was anti-materialist when I was younger, I’m much more materialistic now. More prepared to sell my soul. If you need the money, you should do almost anything…’ She smiles enigmatically. ‘Maybe we should have another bottle of wine. Maybe then I’ll really start weeping.’ Mirren’s father died suddenly from a heart attack. ‘He’d just retired. Got himself an allotment. Enrolled on a writing class. I was doing The Duchess of Malfi at the Roundhouse at the time, in the late Seventies. My understudy had just said, “Don’t ever be off, because I don’t know my lines.” Two minutes later my mum called and said, “Dad’s dead.” My knees just went. Buckled. I was kneeling on the floor. If anyone had seen me, they would have thought I was being far too hammy. I didn’t want to let the cast down so I went on.

But the play is all about death. I did it like a zombie, monosyllabically, crying all the time, even during the opening scenes where I am supposed to be happy and in love.’ Though Mirren has won any number of awards and played the lead in Prime Suspect (the long-running television drama that at the peak of its popularity attracted 17 million viewers), she said not so long ago that she would give anything to know what career satisfaction feels like. When I ask her why she keeps coming back to theatre she says with a laugh, ‘The pleasure lies in one’s obituary. You hope that they will take you more seriously. More brownie points for theatre. What the f- else are you doing it for? Two hundred pounds a week?’ The cynicism isn’t entirely tongue-in-cheek. Mirren even feels disillusioned about what many regard as her most powerful film performance, in Some Mother’s Son (1996), a controversial portrait of the 1981 IRA hunger strike, directed by Terry George. ‘I put a lot of personal effort into it,’ she says. ‘One of my relationships was with an actor from Northern Ireland [Liam Neeson, whom she met on the set of Excalibur in 1981]. And I had spent time there, but, like everyone else, I knew f- all about the situation, really. I wanted the film to reflect all the confusions and contradictions of a civil war, but I got so much flack for it. Only anti-IRA propaganda is acceptable to some political commentators. They consider it a taboo to portray the enemy as human. But I wasn’t an apologist for the IRA. I was in Manchester when that bomb went off and so I saw first-hand how disgusting and pathetic and creepy terrorism is. I got to a point where I just thought, f- the lot of them. Both sides. It’s such a small, parochial part of the world and yet they are so f-ing full of their own self-importance. They are all drama queens.’ Although Helen Mirren is engaging company – by turns passionate, amusing and insightful – I get the impression that there is, at her core, a certain gnawing discontent and emptiness.

She once revealed that, from the age of 18 to 30, she cried herself to sleep every night. ‘I had happiness here and there,’ she now says, ‘but overall, I was insecure. Afraid of the future, not knowing what direction I should take… My parents didn’t want me to get married, so in a sense, I was being a conformist. They were happily married themselves but they didn’t necessarily see it as something everyone should do. When I was about 22 and it became evident I was going to bed with men, then there was a tricky time with my parents. They disapproved. They thought I was being taken advantage of. I wasn’t. They were especially upset because my first boyfriend was Jewish. This was a bit hypocritical considering they had been on the anti-Mosley marches. And, anyway, they liked to think of themselves as bohemian. At those moments people become illogical, emotionally out of control.’ Did she later come to believe in the concept of free love? ‘I suppose people have this image of me f-ing everyone, but actually I’ve only really ever had a handful of long-term serious relationships – though I wasn’t always faithful within those relationships. I always saw the guys I was with as being… well, it wasn’t all to do with sex. That wasn’t the primary thing.

They all taught me stuff I didn’t know. Brought me on. I am like I am because of those men.’ Certainly, in so far as she has rejected the Victorian view that woman shouldn’t appear to enjoy sex, Mirren seems to have embraced the Sixties ethos of sexual liberation. She recently confided to another journalist that she sets her alarm clock an hour before she wants to get up, so that she can make love to her husband. Liam Neeson once said of her that he had been warned she was a ‘maneater… I had read somewhere that when she fancies someone, she imitated the way they walked. One day from the corner of my eye I saw her imitating my big, loping walk.’ Where does she think her image as a woman of prodigious sexual appetite comes from? ‘People are mysterious and you should never read a book by its cover. The most overtly sexual woman are probably really dull and mousy in bed.’ She tilts her head, meets my eyes and adds slowly, enunciating each syllable: ‘You know, I don’t mind watching people f-ing in films, but I remember I used to get really embarrassed about people kissing. It seemed so disgusting.’ Her candour is disarming, especially when she is talking herself down. ‘When I was young I used to get steamed up, bolshy and inarticulate when men patronised me. Now I realise I wasn’t that smart anyway. I didn’t really know what I was talking about. I would have loved to have gone to Oxford but I was too lazy and insecure. I still am. Every New Year’s Eve I make the same resolutions: that I must confront things, be more assertive, make the phone call, meet the person. But I never keep them.’ A friend of Helen Mirren described her to me as being charmingly loopy and fey one minute, commanding, regal and hardheaded the next.

In the four hours I am with her, she seems confident, funny and self-deprecating, yet she also relates how insecure she feels about money and her appearance, and even how she has recurring dreams about being chased by Nazis. So which is the real Helen Mirren? ‘Maybe I’m just good at appearing composed in interviews. I’m not confident about the way I look. I have spent a lot of my time wishing my legs were longer, and my hips weren’t so enormous, and my eyes were bigger and my hair thicker, and my lips shorter. It’s just I know I can’t change these things. As an actor it’s especially hard because you have to be in the make-up chair at six in the morning, staring at your face in the mirror, knowing that everyone else is going to be staring at it for the rest of the day. As an actor you always feel neurotic, you fear you are not tall enough, beautiful enough, good enough, young enough, funny enough, mature enough. When I watch myself in a film, I feel so exposed and vulnerable.’ Acting offers few consolations, it seems. When Mirren is engaged in real-life emotions she catches herself making mental notes. ‘It’s awful, awful. You find yourself experiencing the moment but, at the same time thinking, “I must remember this, what it feels like.” A lot of acting is about recording real moments in your life, but you feel like a real shit for doing it sometimes, and you try and stop yourself.’ Does she ever find herself employing acting techniques to smooth out emotional conflicts in real life? ‘I don’t think so. I’m a really bad liar. Not a very good actor in real life. People can always tell when I’m pretending: I go red and have to confess immediately…’ She trails off. ‘Look, Nigel, I hate talking about acting. I become so inarticulate.

But what I’m trying to say is that it’s not about falsity and putting on a disguise, it’s more about taking off disguises and revealing yourself. It’s about combining technique with instinct.’ That doesn’t sound so inarticulate to me. In fact, it is consistent with something Adrian Noble, the artistic director of the RSC who worked with her on Antony and Cleopatra, has said of her technique: ‘Her sense of how to hold or push the pace, of how to convey a nuance is consummate, but you never see the cogs turning.’ Helen Mirren once described herself as ‘being famous for being cool about not being gorgeous’. I mention that the way she played Detective Chief Inspector Jane Tennison as an exhausted, sour-faced misery, showed an heroic lack of vanity. ‘I tried to look as glamorous as I could! I was wearing loads of make-up. I had my hair cut by Trevor Sorbie. I wasn’t unvain at all. I’ll tell you what it was, Lynda La Plante [who wrote Prime Suspect] had given me a brilliant piece of advice on how to play the role: don’t smile. As a woman you smile and nod and look interested as a salve and a sop and as a way to get round people. Women grow up – God knows why – imagining that their job is to make men feel good about themselves. So Tennison was not there to make you feel good. She wasn’t there to stroke your ego.’ Helen Mirren drains her glass and smiles. I drain mine, turn off my tape recorder and walk her back to her flat, before saying goodnight.